If you are like me, you know many details of your mother’s—or father’s—life. But there may be many vague relationships between this event and that event, between causes and effects. In other words, your parent’s life may end up seeming a mishmash of dates and facts and impressions and none of them blending very well together.

Being a person who has always been interested in family history, I considered myself aware of my mother’s and my father’s lives. Having worked with people to write memoirs, I wanted to be sure that I was not caught, as so many people have been, with not getting my parents’ story while the story was still available—which it wasn’t in my father’s case as he was deceased.

I begin to write

In 2009, I began to focus on interviewing my mother. Every few weeks (she lived in a different city), I would visit with her and get in a half hour interview. Since my mother was not primarily interested in preserving her life story (it was my interest), she was not committed to a beginning-to-end interview process. What I ended up doing was simply asking her questions—often in a conversation. Once back home, I would write down her answers to my questions.

My mother did not always sense that I was interviewing her for her memoir. Every once in a while however, I specifically had to inquire, “When was the date that you did this or you did that?” or “Which came first: this event or that?” In those moments, she became aware that I was continuing to write her memoir.

Tweet: My mom asked, “Why are you writing my memoir? Who will want to read it?”http://bit.ly/1dyT1Ju

She also might say, “How in the world are you going to find enough information to fill the pages of a book, even a small book?”

Since I was also working full-time at my company Memoir Network, writing my mother’s book fit in around the edges of books that I was editing, coaching, ghostwriting. and teaching. In short, it fit around my income production. This process is not unlike how most people will write either their own memoir or the memoir of a loved one.

The memoir continues to grow

Over the next four years, I interviewed my mother and wrote text. When my mother gave up her apartment and moved into an assisted-living facility, I knew the leisurely pace at which I had been writing had to change. I applied myself to completing the memoir and set a time for finishing. I had wanted to get to a later point in her life as the ending.

However my mother’s ability to contribute to the story was diminishing. She had less of a grasp on specific details, on dates, on who was there and who did what when. I opted for a different end point than I had anticipated, one that was closer to the time of the text that I had already written. This proved to be a good closing point even if it was disappointing to three of my siblings whose birth did not make it into the memoir. (I mentioned them in an afterword.)

What did I get from writing my mother’s story?

I got acceptance of her life, a sense of who she was, and that who she was was just fine.

Writing my mother’s memoir gave me the opportunity to get to know her in an intimate way that I had not had the opportunity to before. Her past had been vague; the setting of her life not at all clear; the sequencing of events haphazard at best.

There were a few occasions in my mother’s life when her response was a hero’s response, when she rose to the needs of an occasion that was difficult to live. She conducted herself well in those circumstances. That is a hero’s response. But the bulk of my mother’s life was yoeman’s work, pick and shovel work. It consisted of making a home, going to work, raising children and so forth. It was day-after-day work. Now this may be hero’s work of a certain kind but it turned out that it was a rather humdrum and ordinary sort of work. In a way, my mother’s life helped me to understand and to accept my own yeoman’s work.

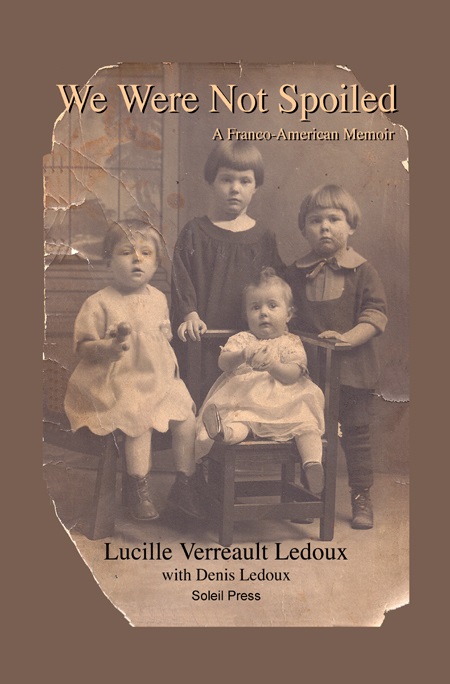

In time, I produced a book I called We Were Not Spoiled: A Franco-American Memoir.

Finally, the hard copy was finished and I showed it to my mother.

As I wrote her life, one task that was important to me was to fit her life into a cultural, social, and historical context.

Large parts of the 208-page book have to do with her time, with cultural or historical events. For instance, there was a flood in her city in 1936. Briefly I wrote about that flood. There were developments in the political life of her city that affected her. I also dealt with these on occasion. There were historical contexts that made for why she lived where she lived.

Many details having to do with our ethnicity, details that distinguished her adaptation to American life from that of members of other groups, found their way into the book. My mother’s bigger picture was one that was familiar to me and it was not difficult to place her life in that larger context.

Because of this bigger picture, the book proved to be of interest to more people than my mother anticipated. We Were Not Spoiled: A Franco-American Memoir has been sold on Amazon and has attracted comments either in the review section or in emails that people have sent me saying, “You wrote my mother’s life! How did you know her so well?” This, of course, is a fun note to receive.

Go ahead and commit to writing. The benefits are well worth the effort that you will have to expend.

Good luck.

Denis Ledoux is also the author of Write to the End: Eight Strategies to Thrive as a Writer (Memoir Network Writing Series Book 4)and Don’t Let Writer’s Block Stop You: How to Push Beyond Stuck (A Memoir Network Writing Series Book 3)

Receive free downloads at My Memoir Education.

===========

Please note that some links on this blog may be affiliate links.